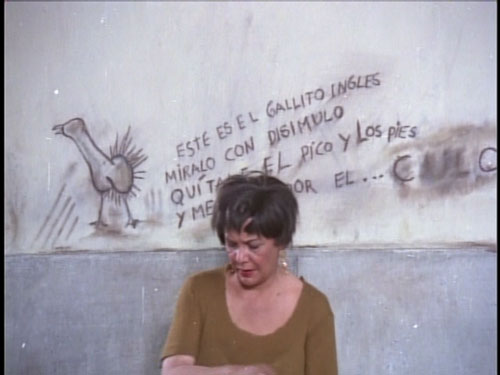

English greyhounds may be inferior their Iberian cousins (and Scottish dogs similar to bears), but the English have tended to excel at the breeding and training of sporting beasts, including Portuguese racing sardines and, before blood sports fell out of fashion, the game cock. Here’s the full version of the Mexican tribute pictured above:

Éste es el gallito inglés

míralo con disimulo

quítale el pico y los pies

y métetelo por el culo.

Or:

This is the English cock

Nibbling in the grass

Take off its beak and feet

And stick ’em up your arse.

Gallus anglicus (“gallo de raza fina, que pelea mucho‎”) seems to have started to become the cosmopolitan sportsman’s preferred fighting cock in the late 18th century, just as, for related reasons, British military and particularly naval power approached its long zenith. The Mirror of literature, amusement, and instruction in 1823 contains a strategic identification of gallus with phallus:

The following anecdote of an English game-cock, so well portrays the nature of that bold and martial species of animal, that it is worthy of being recorded. In the justly celebrated and decisive naval engagement of Lord Howe’s fleet with that of France, on the first of June 1794, a game-cock on board one of our ships, chanced to have his house beat to pieces by a shot, or some falling rigging, which accident set him at liberty; the feathered hero now perched on the stump of the mainmast, which had been carried away, continued crowing and clapping his wings during the remainder of the engagement, enjoying, to all appearance, the thundering horrors of the scene.

So what, in fighting terms, was special about these birds? François Rozier serves up some classic Gallic sour grapes in his Cours complet d’agriculture, issued with royal approval in the nick of time in 1789:

These birds are no bigger than ours, but they are higher slung [plus haut montés]. Their legs and feet are much longer. That is the only difference.

Height, reach, and great big feet are no mean advantage for a fighting bird, but their courage also contrasted favourably with that of continental birds. Take for example the Spanish fowl (gallo andaluz/Minorcas/Portugal fowl/Black Spanish fowl):

This is a noble race of fowls, possessing many great merits; of spirited and animated appearance, of considerable size, excellent for the table, both in whiteness of flesh and skin, and also in flavor, being juicy and tender, and laying exceedingly large eggs, in considerable numbers. Amongst birds of its own breed, it is not deficient in courage; though it yields without showing much fight to those which have a dash of game blood in their veins. (The American poultry yard (1850))

The binary opposition of English and Spanish fowls as a metaphor for the contrast between growing British military might and noble but increasingly incompetent Spanish forces is hinted at in early 19th century popular literature–for example in this story from Doce españoles de brocha gorda by the minor costumbrista, Antonio Flores:

Su cuerpo tirante, sus manos gafas, los bordones del cuello tirando de los carrillos, y su cabellera crispada en masa, gracias á que la peluca era repelida del cráneo, mas parecía don Pepito un gallo inglés que un marica español, gente de suyo pacifica y esponjosa.

I’m pretty sure this opposition was a direct import from France, paradoxically just as revolutionary nationalists were trying to establish the rooster as the symbol of France as a nation and its history, land and culture.

[Aside: The origin of the association, suspiciously similar to that of Gregory the Great’s “Non Angli, sed Angeli” salvation of the Angles, is linguistic: Suetonius’ pun on gallus to describe both a cockerel and an inhabitant of Gaul:

Au début du Bas Moyen Âge (XIIe), les ennemis de la France réutilisèrent le calembour par dérision, faisant remarquer que les Français (tout particulièrement leur roi Philippe Auguste) étaient tout aussi orgueilleux que l’animal de basse-cour. Par esprit de contradiction, les Français reprirent à leur compte cette expression en mettant en avant ce fier animal.

Bien que présent comme figure symbolique en France depuis l’époque médiévale, c’est à partir de l’époque de la Renaissance que le coq commence à être rattaché à l’idée de Nation française qui émerge peu à peu. Sous le règne des Valois et des Bourbons, l’effigie des Rois est souvent accompagnée de cet animal censé représenter la France dans les gravures, sur les monnaies. Même s’il reste un emblème mineur, le coq est présent au Louvre et à Versailles.

But

Le coq gagna une popularité particulière à l’occasion de la Révolution française et de la monarchie de Juillet, où il fut introduit en remplacement de la lys dynastique.

]

An fine example of French use of the proud English cock vs is to be found in Le coq anglais, one of various patriotic war fables written by Pierre-Laurent Buirette de Belloy. It kicks off with the popular proverb, “Il fait bon battre un glorieux, il ne s’en vante pas” (It’s good to beat a vain man–he won’t boast about it), and then refers to Byng’s failed attempt to break the French siege of Minorca and subsequent British attempts to save face by downplaying its strategic importance, as well as what sounds like another engagement which I can’t however immediately identify:

LE COQ ANGLAIS

Il fait bon battre un glorieux,

Il embourse vos coups de gaules

Avec un oeil sec et joyeux;

Puis en pleurant, chez lui va frotter ses épaules.Un Coq, Anglais de Nation,

De cette vérité fournit preuves complettes.

Jamais ces meisseurs d’Albion

Ne conviennent de leurs défaites:

Témoin la perte de Mahon,

Dont s’applaudissent leurs gazettes.

Ce Coq à lui seul desservait

Un charmant cloître de Poulettes,

Comme un Carme dessert un couvent de Nonnettes,

Peut-être mieux encore. On dit qu’il en avait

De toutes les couleurs, de blondes, de brunettes;

Sa Cour était un vrai serrail.

Sans Eunuque pourtant, sans ce noir attirait

D’Afriquains à mine enfumée,

Que l’on ne connaît pas chez la race emplumée;

Quoique notre Sultan eût assez de travail

D’aimer tout ce gentil bercail,

L’Amour lui fit sentir encore une étincelle

Pour une poule jeune & belle,

Qui faisait la félicité

D’un Coq voisin qui n’avait qu’elle.

J’ai dit l’Amour; mais non, c’était la Vanité;

Il en était tout plein, et sa fatuité

Lui faisait présumer qu’heureuse de le prendre,

A ses premiers soupirs la belle allait se rendre.

Telle manière de penser

Est, je l’avoue, un peu Française:

Mais à Douvres, l’Escadre Anglaise

N’empêche point nos défauts de passer,

Ils ne sont pas censés de contrebande,

Et vont droit de Calais, sans l’entrepôt d’Ostende.

Un marin donc il s’en va la trouver,

Lorsque l’aurore était à son petit lever:

Lui picottant le bec, doucement il l’éveille

A petit bruit, lui jargonne à l’oreille,

Il se rengorge, il fait le beau,

D’un air vainqueur, ses ailes il étale,

S’en bat les flancs, puis s’en fait un manteau,

Mais un manteau traînant à la Royale:

Bref, il fait tant, dit tant, et caquette si haut,

Que le mari se réveille en sursaut,

Et fond sur lui comme un tonnerre.

Voyez-vous pas son bec sanglant,

Qui fait voler, du beau galant,

Plumes en l’air, crête par terre,

Et vous le chasse nud, vergogneux et tremblant?

Le pauvret fuit, et dans la route ,

Se voyant seul, il gémit librement,

Soupire & pleure amèrement

Ce que son sol orgueil lui coûte :

Comment paraîtra-t-il en ce piteux état?

Comment cacher sa honte et ce fatal combat?

Comment, enfin sans queue, aborder ses poulettes?

Pendant qu’il réfléchit, il les voit accourir,

Qui, de son absence inquiètes,

Avaient fait, pour le découvrir,

Tout au moins un grand quart de lieue.

Eh! bon Dieu! comme vous voilà!

Qui vous a donc plumé comme cela?

Vous n’avez plus de crête, où donc est votre queue?

Calmez-vous, leur dit-il en fouriant, je vien

De chez notre Baigneur & notre Chirurgien :

Je me suis fait ôter cette maudite crête,

Qui depuis si long-temps m’embarrassait la tête,

A quoi me servait-elle? A me faire accrocher

Par la moindre petite épine;

Vous l’avez vue encore avant-hier s’arracher

Sur un des clous de la treille voisîne.

C’est par prudence aussi que je me fuis défait

De ce pesant manteau de plumes,

Qui si cruellement dans l’été m’échaussait.

Cette prudence-là vous vaudra de bons rhumes;

Dit une Poule: allez, nous vous croirions, mon cher,

Si nous n’étions en plein hiver.

Not quite as telling as “il est bon de tuer de temps en temps un amiral pour encourager les autres”, but De Belloy apparently said somewhere that “the best thing about man is the dog,” so give him a chance.

Psycho-sexual-cultural studies geezers tend to jump up and down with delight when el gallito inglés comes up because of what they see as the “explicit sexual threat of anal rape” (Jan M. Ziolkowski, Obscenity: social control and artistic creation in the European Middle Ages). They invariably miss, to their disadvantage, the slightly abstruse pun {inglés:ingles=English:groins}. In their rush to pin yet another vice to English masts they also ignore the clear but for them inconvenient implication of auto-infliction, and the casual and non-threatening use of dick ‘n’ ass metaphors in children’s tales like Medio pollito/Demi coq, in which the protagonist of one popular version stuffs a pile of stones, a vixen and a river up his arse. El gallito inglés was, after all, a children’s game in (post-war) Spain (check for example the little girls in Maite García Romero Ora pro nobis), at a time when infant sodomy wasn’t generally encouraged. And I take it that this tyre business in El Paso isn’t a front for a Mexican gay SM brothel.

If it keeps on raining then I hope to post some more cock and bull soon, this time of more general interest.

Similar posts

- Competition videos from the Portuguese Racing Sardine Club

The British Sardine Racing association (popups) is “dedicated to breeding a better Sardine, revolutionising training methods, and the breeding of - Free English-language Iberian climate atlas

Authored by the Spanish and Portuguese state meteorology services, an 80-page PDF with a good range of temperature and precipitation data - Madrid Olympic bid scuppered by constitutional chaos?

Is Spain a federal state? Is Arenys de Munt the new Andorra? Can I pay taxes to anyone I want? - Bear-faced cheek

These bloody bears, they come over here and everything get’s changed just to suit them. Do bears shit in woods? Yes, - Complicated family joke

Displaying Mexican contempt for the

I gugled a bit and came up with a nice pamphlet from 1659 called A Character of France to which is added, Gallus Castratus: Or, An Answer to a Late Slanderous Pamphlet, called the Character of England, the latter being ascribed to John Evelyn. So a century earlier it sounds like no attempt has yet been made to appropriate the rooster for brand Ingerland. The French revolutionary cock is surely an attempt to regain the bird from the English and modernise it, a bit like the Cool Britannia reappropriation of the Union Jack from the NF.

So the pre-revolutionary Gallic rooster was a gorgeous 12th century Renaissance bird, while its 18th century English rival was a vulgar mercantilist creature, perhaps rather like a herring gull.

Re gallus castratus: some doubt exists as to whether an English cock could technically be castrated–a plumber once told me that {cock=penis} came from the resemblance of the (his example of the) latter to the stopcock; his girlfriend was something of a spiggot, too.

EL GALLITO INGLÉS

desde pequeño siempre ha estado a mi lado

crecimos juntos siempre fue muy bien portado

o el es un gallo le digo el gallito ingles

siempre conmigo aunque no siempre lo ves

es el gallito ingles

es el gallito ingles!

a este gallito les encanta a mis gallinas

de vez en cuando me lo piden mis vecinas

el nunca duerme todo el dia esta bien parado

muy limpiecito y muy bien asi calado

es el gallito ingles

es el gallito ingles

quien es?quien es?

es el gallito ingles

(otravez)

ese gallito es un gallito muy fino

y en las peleas siempre ha tenido buen tino

en nunca cae siempre ha sido muy potente

el lo termina hasta cansar al oponente

esta es la historia de mi gallo consentido

nunca lo presto mucho menos te lo pido

el es muy grande pero sigue como nuevo

si yo me muero yo conmigo me lo llevo

es el gallito ingles

es el gallito ingles

quien es? quien es?

es el gallito ingles

(se repite)